"Bank-grade" security is bullsh*t

When companies say they have 'bank-grade' security, it implies that this is the pinnacle of cyber safety. In reality, it couldn't be further from the truth.

You’ve been tricked into visiting dodgy websites before, right? Maybe you were winding down one night with a bit of online retail therapy and stumbled onto some knock-off version of a big brand’s store. It looked convincing, had a padlock in the address bar, and maybe even wore one of those “This website is safe—trust me bro” badges from a big-name certificate authority.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: it’s totally possible to scam someone securely.

This is the problem with relying on surface-level signals like certificates or buzzwords like “bank-grade security.” They’re easy to slap on, but they don’t tell you anything meaningful about whether the site is truly protecting users where it counts.

Just because a website is secure, doesn’t mean it’s safe. If there's nothing behind it, then it's just security theatre.

I’m just going to say it: if you’re responsible for a web-based system, then protecting your users and their data isn’t optional. It’s your responsibility. End of story.

I know that’s a punchy way to open, but it needs to be said, because too often, I see people throw a TLS certificate on their site and call it a day. Box ticked. Job done. But a cert is a start, not a solution. What we need is a mindset shift toward proper defence in depth, because that's where real protection lives.

This post is about going deeper. We’re going to explore beyond the padlock into what actually makes a web app secure, by looking at the tools, headers, and controls available in modern browsers and web servers.

I’ll cover what they are, why they matter, and how to implement them properly—because real security isn’t a single checkbox. It’s layered. It’s intentional. And most importantly, it’s in your hands.

A quick HTTP/S primer

When you connect to a website over plain old HTTP, there’s no verification to confirm that the server responding to your request is actually the real deal. The browser just assumes it’s talking to the right web server, and from there, everything is transmitted in clear text—no encryption, no protection, no questions asked.

Why HTTP is a terrible idea in 2020

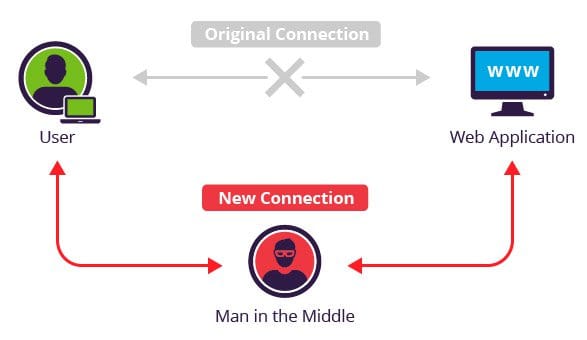

The biggest problem with HTTP is that all your communication is sent in the clear. That means anyone sitting between you and the server—someone on the same Wi-Fi network, your ISP, or even a government agency (hi, NSA)—can quietly listen in. Think of it like a digital wiretap. An eavesdropper can see what sites you’re visiting, what you’re typing, and what the site sends back to you.

This type of interception is called a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack, and it’s a lot easier to pull off than most people realise.

Now, you might not be too fussed if someone sees you browsing news headlines or reading dad jokes. But things get sketchy fast the moment sensitive data enters the mix—like logging into your bank, entering personal info, or submitting a form on a website you'd be too embarrassed to show your parents.

Since there’s no server verification and no encryption, you could think you’re logging into your bank—but you’re actually being redirected to a lookalike site designed to harvest your credentials.

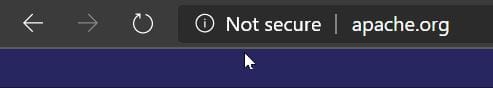

Because this type of attack is both trivial to execute and deeply impactful, modern browsers have started taking a stand. Many now explicitly mark HTTP connections as “Not Secure”—because, well, they aren’t.

Enter HTTPS: Actually trying to keep you safe

As the internet matured, the need to protect data in transit became more than just a good idea—it became essential. Users were submitting passwords, credit card numbers, and personal information online, and plain old HTTP simply wasn’t up to the task. To address this, HTTPS was introduced as an extension of the HTTP protocol that supports encrypted communication using Transport Layer Security (TLS).

This was formalised in RFC 2818, which describes how HTTP can be layered over TLS. TLS itself is the successor to SSL, which is now deprecated due to significant security flaws. Despite this, you’ll still hear people refer to “SSL certificates”—old habits die hard I guess.

The "S" in HTTPS stands for Secure, and it does what HTTP doesn’t: it encrypts your connection so that data can’t be easily snooped, tampered with, or redirected without detection. That little padlock icon in your browser’s address bar? That’s your visual cue that HTTPS is in play—though, as we’ve seen, it's not the full story when it comes to trust.

To run HTTPS, a web server needs to install a digital certificate. These SSL/TLS certificates are small data files that do two important things:

- Authenticity – They prove the server you're talking to is actually who it claims to be (via the organisation’s identity).

- Encryption – They enable the use of public/private keys to encrypt the traffic between the browser and the server (see Public Key Infrastructure, or PKI).

Together, these things ensure three key principles:

- Confidentiality – Connection is private and no one else can read your traffic

- Integrity – The data hasn't been intercepted or modified in transit

- Authenticity – You’re talking to the right server.

When those three are in place, we reach what infosec folks call non-repudiation—basically, proof that the communication happened and wasn’t messed with, forged, or denied after the fact.

How Web Security Has Evolved

Not too long ago, SSL certificates came with a price tag. You’d pay around $100 for a single-domain certificate, a few hundred for a multi-domain setup, and if you needed a wildcard cert? That could run into the thousands. Because of the cost, HTTPS was typically reserved for websites dealing with sensitive transactions—banks, online shops, login portals. Everyday sites like blogs, forums, or news outlets usually didn’t bother. Why pay for a certificate when there’s “nothing to protect”?

And this is where the thinking was flawed.

Even if a site doesn’t handle sensitive data, the user is still at risk. Whether it’s a comment on a blog post or a banking login, the connection itself can be intercepted, and the risk to the user has not changed. The user is just as vulnerable to eavesdropping, and cyber-attacks such as man-in-the-middle, phishing and pharming, regardless of what the site hosts.

Fast-forward to today, and the game has changed completely. Thanks to organisations like Let’s Encrypt, the cost barrier has disappeared. Certificates are now free, automated, and easy to deploy. This move democratised HTTPS and triggered a massive shift toward secure-by-default web practices.

One of the strongest signals of this shift comes from Google. Through their Chromium browser engine, they’ve been steadily changing the way HTTP is treated. The plan? Mark all non-HTTPS pages as affirmatively “Not Secure”. No padlock. No mixed signals. Just a clear message: if a site isn’t using HTTPS, it’s not safe to trust.

Your Responsibility to Your Users

Your job doesn’t stop at locking down your backend systems or protecting stored data. It extends to the people using your site—your visitors, your users, your customers. You have a responsibility to help protect them, too.

That means writing code with secure development practices, not just ticking the certificate box. It means defending against known threats like SQL injection (SQLi), cross-site scripting (XSS), and other attacks that target your app’s behaviour—not just its infrastructure. And yes, it absolutely includes securing the data in transit with HTTPS.

But beyond the basics, there’s a whole suite of additional controls you can implement. Ther are a number of small configuration changes that can significantly reduce the risk of exploitation. These are things that cost you next to nothing but deliver real protection to your users.

And here’s my view: if you can take steps to protect people using your application, and those steps offer clear, measurable security benefits, it’s irresponsible not to.

“A person may cause evil to others not only by his actions but by his inaction, and in either case, he is justly accountable to them for the injury.”

— John Stuart Mill

This mindset—that you owe your users a proactive approach to security—is something sorely lacking in an industry still throwing around the phrase “bank-grade security” like it means something.

“Bank-Grade” Security: Not Exactly a High Bar

When companies claim they offer “bank-grade security” it’s meant to sound impressive, like this is the gold standard of cyber safety. But in reality? That phrase is doing a lot of heavy lifting for what often turns out to be the bare minimum.

Let’s put it to the test.

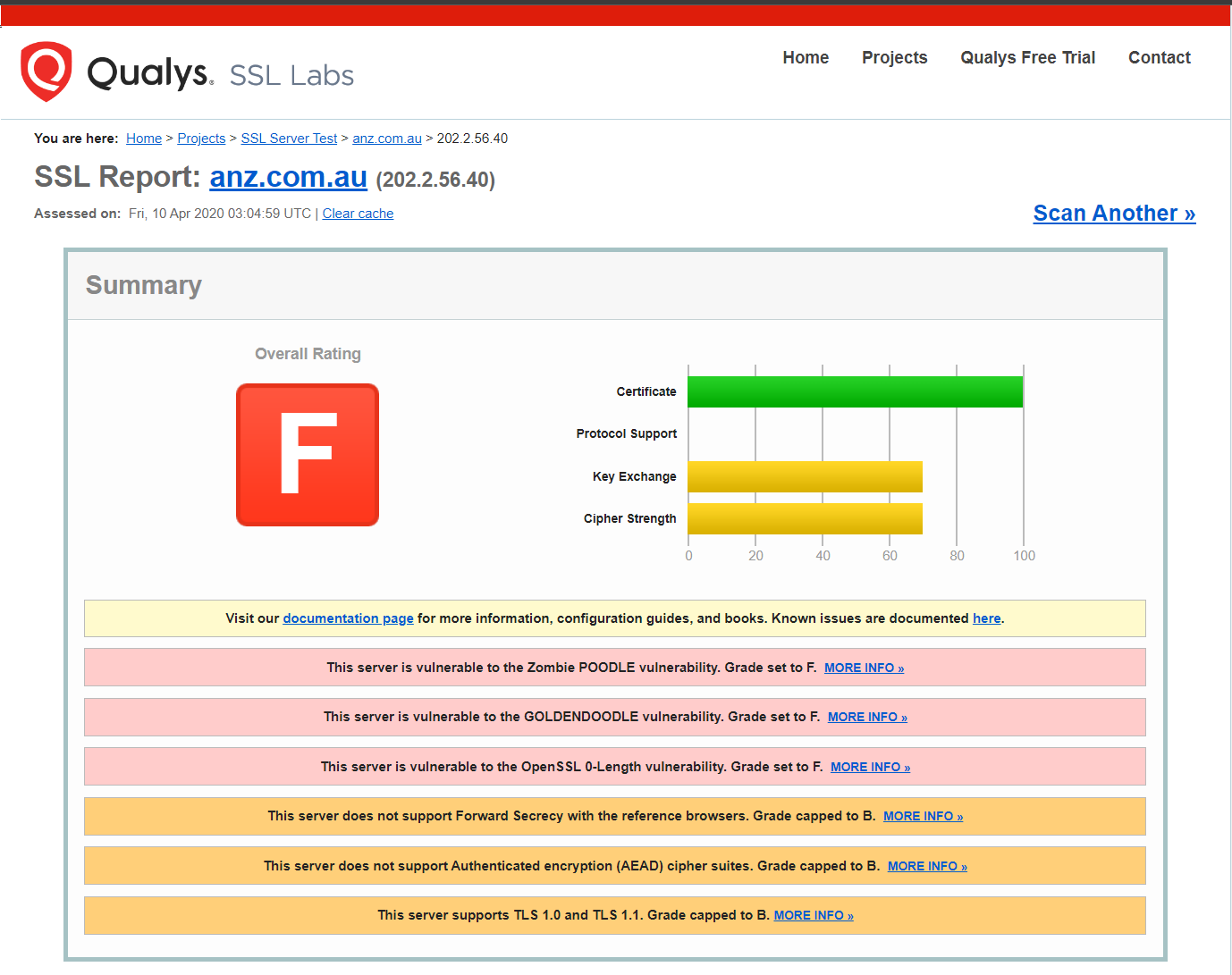

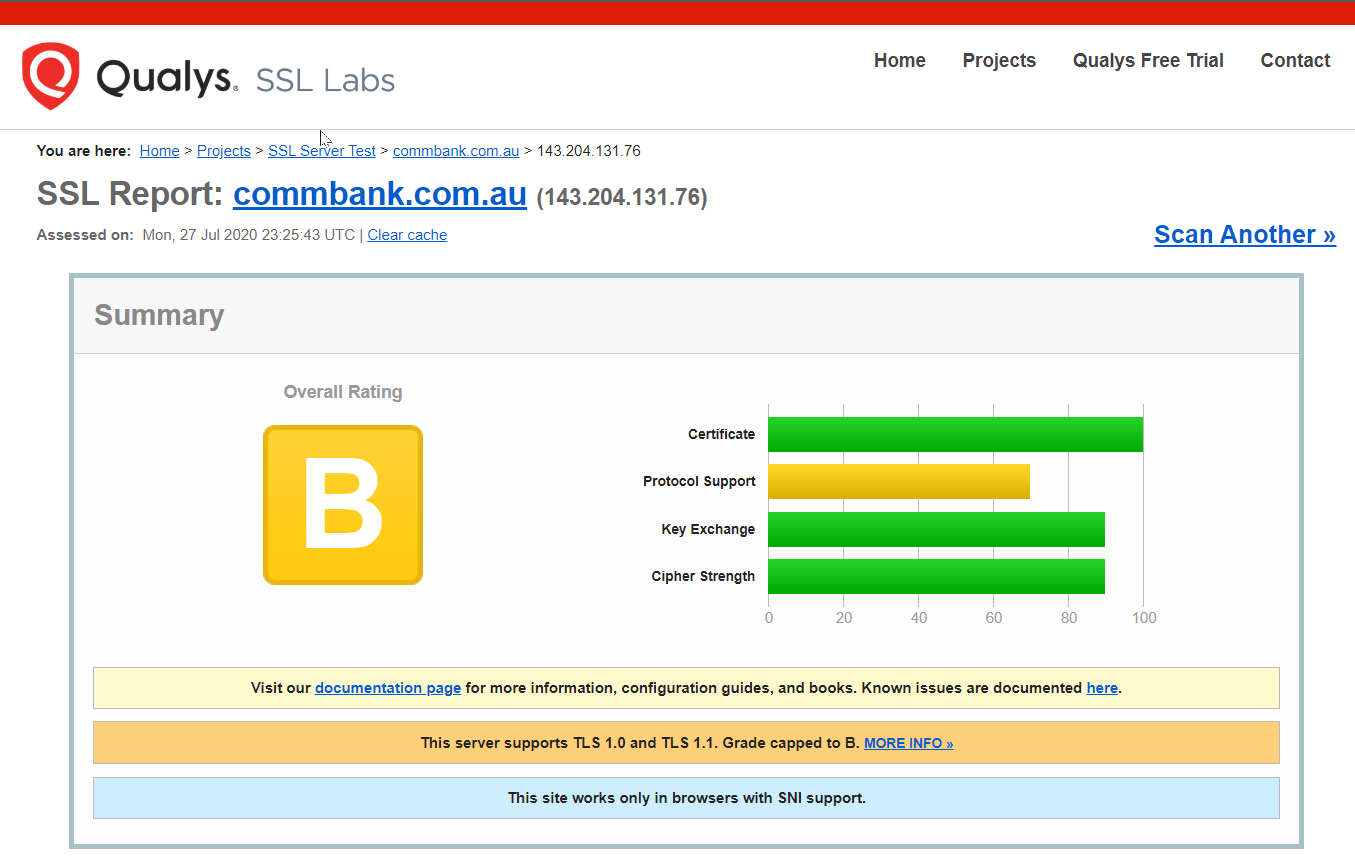

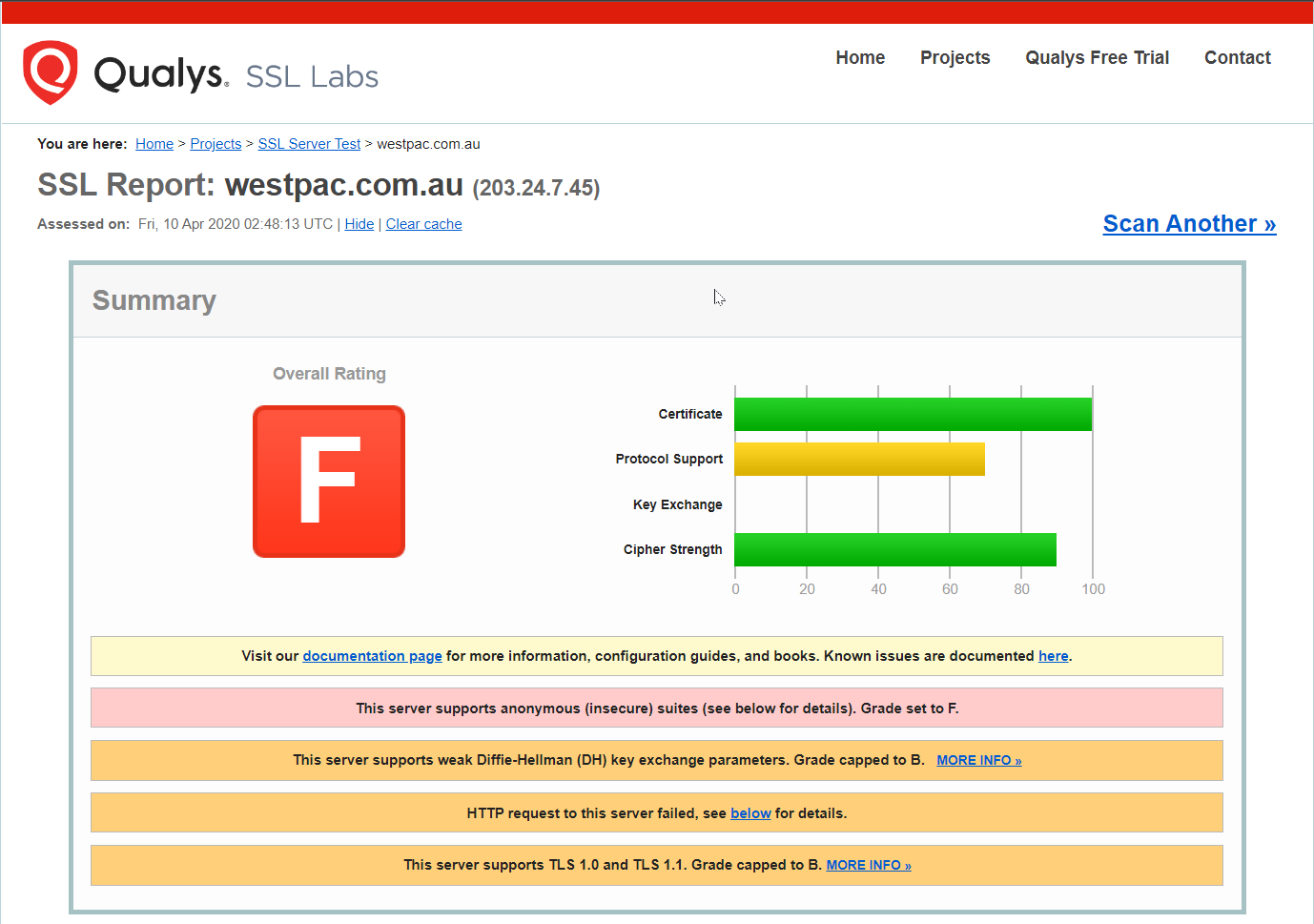

Here are SSL Labs reports for Australia’s “Big Four” banks:

SSL report for the Australian "Big Four" banks

Of the four, NAB is the only one pulling a respectable grade. The others? Pretty terrible if you ask me. Which is kind of the point: if this is what “bank-grade” looks like, we need to stop treating it like some kind of untouchable benchmark.

As a consumer, you should expect better. And as someone running a web app or service, you can do better.

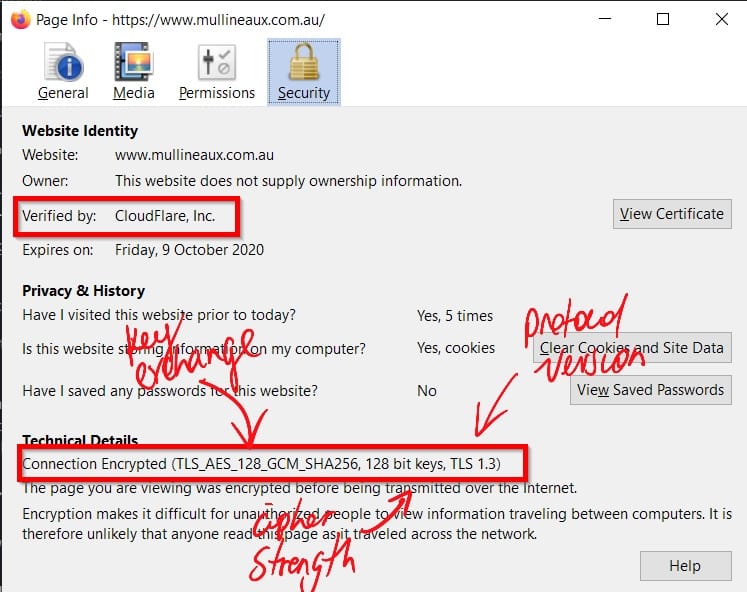

To prove I’m not just taking potshots from the sidelines, here’s the same SSL Labs test run against this very website:

There’s a lot that goes into properly securing the communication between client and server, and we’re going to get into it. But first, let’s break down the key components that define strong SSL/TLS security, starting with certificate strength.

SSL Certificate Strength

Securing the connection to your website takes more than just slapping on any old certificate. During certificate generation, several key decisions determine how strong (or weak) your encryption actually is. These include:

- Cipher strength (e.g. SHA-256):

This defines the cryptographic algorithm used to sign the certificate and encrypt data. The larger the bit size, the more difficult it is to crack via brute-force. Outdated or weak ciphers like SHA-1 should be avoided entirely as it can be cracked with ease with modern GPUs. - Protocol version (e.g. TLS 1.2 vs SSL 3.0):

SSL is the predecessor to TLS and is no longer considered secure. TLS 1.2 and 1.3 are the current standards, with 1.3 offering improved performance and security. Older versions like SSL 3.0, TLS 1.0, and TLS 1.1 are now deprecated and should be disabled. - Key exchange mechanism (e.g. RSA, ECDHE, or Diffie-Hellman):

This determines how the client and server agree on a shared encryption key over a public network. Weak or improperly configured key exchange parameters, especially with older Diffie-Hellman implementations, can expose your site to downgrade or interception attacks.

The way these options are configured defines the overall strength and resilience of your SSL/TLS setup. And like anything in security, these defences need to evolve with the threat landscape. Over time, vulnerabilities are discovered in algorithms, cipher suites, and protocol versions which necessitates updates, patches, and configuration changes to remain secure.

If you’re using a modern certificate provider like Let’s Encrypt or Cloudflare, you’re in good hands. These providers configure everything securely out of the box, with strong defaults and regular updates.

However, if you're generating your own certificates, especially from an internal or private certificate authority, then it's on you to get this right. That includes scenarios where you're using self-signed certificates. Misconfigurations here can leave your site wide open to attack, even if everything looks fine from the browser’s perspective, and even if it's just for a local service never exposed to the internet.

HTTP Security Headers

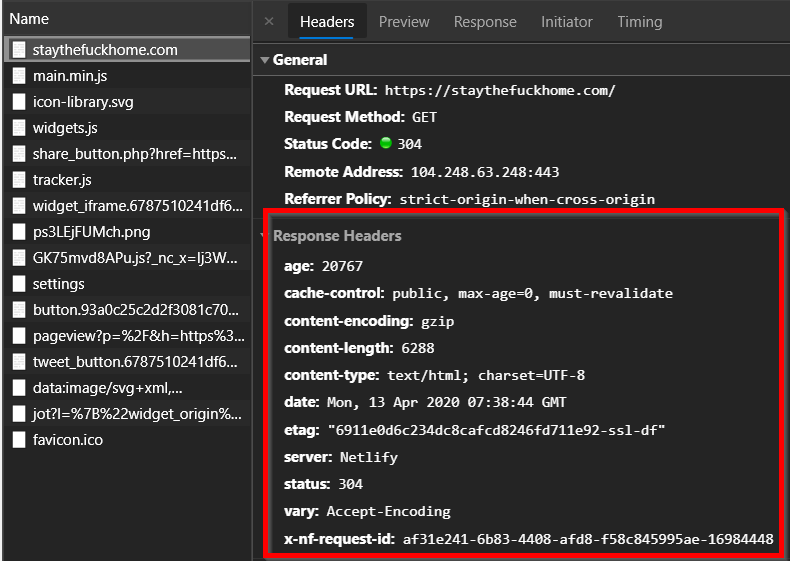

To understand how HTTP security headers protect your users, we first need to take a step back and look at what HTTP response headers actually are.

When your browser requests a page from a web server, the server doesn’t just respond with the content. It also sends back a set of key-value pairs known as HTTP response headers. These headers carry metadata about the response and tell the browser how to handle what it just received.

Response headers might include:

- What type of content is being delivered (

Content-Type) - How long to cache it (

Cache-Control) - What server software is being used (

Server) - Whether the server accepts supports compression, the software running on the server, and so on

Now, security headers are a special class of HTTP response headers. Rather than dealing with caching or content types, they transmit security policies to the browser. By setting these headers, you can control how the browser behaves when rendering your site. Think of these as switches and dials that can be flicked and turned to reduce the attack surface of a website.

For example, security headers can:

- Restrict what features the browser can use (e.g. camera, microphone, geolocation)

- Control where content can be loaded from

- Block your site from being embedded in iframes

- Enforce HTTPS usage or strict transport rules (more on this later)

By including the right security headers, you make your users' browsing experience measurably safer. You reduce the risk of clickjacking, cross-site scripting (XSS), content injection, and other common browser-based attacks, all without touching your application code.

Let's walk through each of the major HTTP security headers, what they do, and how to configure them properly.

Configuring Security Headers

Security headers aren’t set in your app code, they’re a configuration option on the web server that serves your content. That means how you implement them depends on the underlying server technology you’re using.

For example:

- Apache uses

.htaccessor the main config file - Nginx sets headers via

add_headerdirectives - IIS uses

web.configor the IIS Manager GUI

If you're on a hosted platform like Wix or WordPress, many offer tools or plugins to help manage response headers, though the options might be limited or abstracted. Either way, you’ll need to refer to your hosting platform’s documentation to apply the correct approach.

But what if you don’t have access to the server config? Maybe you’re hosting a static site like I am, using something like Jekyll, Hugo, or another static site generator, and your content lives in an object store like Azure Blob Storage or Amazon S3. In that case, it's a bit tricky, but still possible.

You can still apply security headers in transit using services like Cloudflare Workers, AWS CloudFront, or Azure Front Door to intercept and modify the response headers before they reach the user’s browser.

In short: no matter what your hosting setup looks like, there is a way to apply security headers, so there’s really no excuse to skip this step.

Configuring Security Headers

The implementation of security headers is a configuration option that must be done on the webserver that serves the content, therefore the method in which these are configured depends on the underlying web server technology. For example, the method is different for Apache vs Nginx vs IIS. Hosted platforms like Wix or WordPress usually have tools or plugins that let you configure the response headers. You’ll need to research your hosting framework to see the steps that apply to your situation.

If you don’t have access to the webserver for some reason or you’re operating a website that uses static page framework such as Jekyll or Hugo that’s hosted out of a public storage container like Azure Blob Storage or an Amazon S3 bucket, the HTTP headers can be added ‘in transit’ with something like CloudFlare workers.

Basically, there’s a method to apply security headers in any web hosting situation so there’s no excuse for thinking that this doesn’t apply to you.

Hardening Your Site with Security Headers

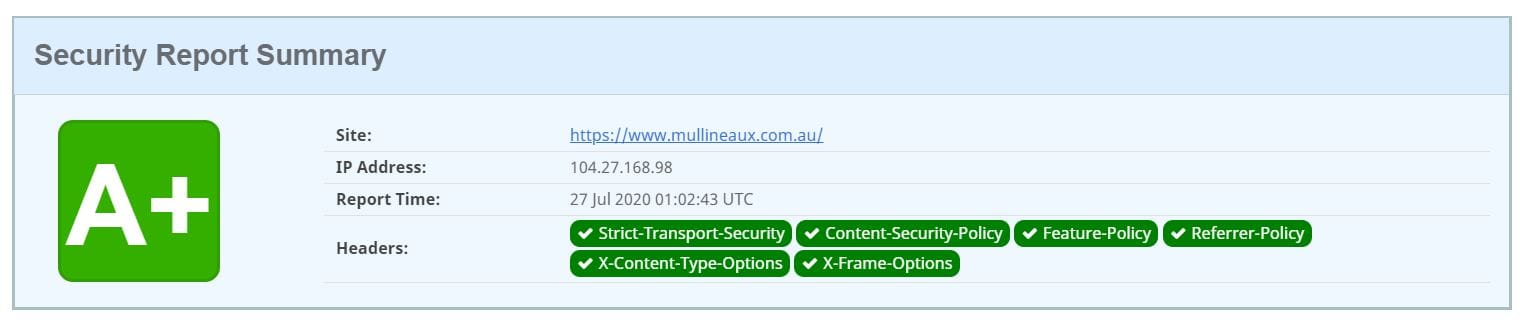

Now that we know what HTTP response headers are and how to implement them, it’s time to dig into the specific security headers that can make a real difference.

These headers give you fine-grained control over how browsers interact with your site. Done right, they can help protect your users from common attack vectors like content injection, clickjacking, and downgrade attacks. And yes, with the right config, you can absolutely achieve a stronger security posture than most banks.

If you want to quickly check how your current headers stack up, run your site through securityheaders.com. It’ll give you an A–F grade and highlight missing or misconfigured headers.

Let’s start with one of the most foundational controls: HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS).

HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS)

HSTS, or HTTP Strict Transport Security, is a security header that tells the browser, “Don’t even think about using HTTP with this site. Ever.” Once the browser sees it, it enforces HTTPS for every future visit, even if the user types http:// or clicks on an old, insecure link.

Why does this matter? Because if HSTS isn’t set, a bad actor could downgrade your visitors to HTTP using an attack like SSL stripping, intercept the traffic, and start siphoning off data. This type of attack is simple, silent, and still surprisingly common on open Wi-Fi networks.

HSTS stops that cold. With one header, you’re telling the browser: "If it’s not encrypted, don’t load it."

Example header: Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000

That sets the policy for one year. You can also add includeSubDomains to cover your whole domain, and preload if you want to go full commitment mode and submit your site to the browser preload list. Just make sure you’ve got HTTPS sorted everywhere first before you do that, or you may run into issues.

Content Security Policy (CSP)

Content Security Policy (CSP) is one of the most powerful security headers you can use. It lets you define a whitelist of trusted sources the browser is allowed to load content from. Think of it as a browser-level bouncer that only lets in files from domains you trust.

A properly configured CSP can protect your site from a wide range of threats, including:

The idea is simple. You set rules — called directives — that tell the browser what kinds of content are allowed, and where they’re allowed to come from. For example:

- Only load JavaScript from your own domain and a trusted CDN

- Block inline scripts completely

- Upgrade any HTTP links to HTTPS automatically

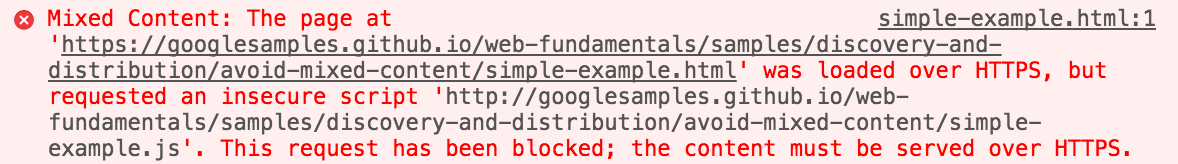

CSP doesn’t just help prevent malicious content from being loaded. It also stops lazy mistakes from becoming security issues. If you’ve accidentally included a link to an insecure image or script, the browser can rewrite it to HTTPS using the upgrade-insecure-requests directive.

This works really well alongside HSTS. HSTS upgrades the initial connection to HTTPS. CSP’s upgrade-insecure-requests upgrades the content on the page that might still be using insecure URLs. Between the two, you’re covering your bases.

Example header: Content-Security-Policy: upgrade-insecure-requests

One important thing to keep in mind is that if you configure HSTS to require all requests to be served over HTTPS, but include HTTP content on your pages without also specifying the upgrade-secure-requests CSP header, you'll end up with mixed content errors on your site.

That’s a simple example, but CSP can go much deeper. You can lock things down to a very granular level. If you want to get serious about it (and you should), the full list of CSP directives is available on Mozilla Developer Network.

X-Frame-Options (XFO)

X-Frame-Options is a simple header with a big impact. It tells the browser whether your site is allowed to be embedded in things like <iframe>, <frame>, <embed>, or <object> elements. This matters because attackers can use these elements to load your site invisibly inside their own and trick users into clicking on something they didn’t mean to — a trick known as clickjacking. With XFO in place, you can stop that cold.

The most common setting is: X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

This means your site can only be embedded by pages on the same domain. You can also use DENY to block all framing completely, or ALLOW-FROM with a specific URL (though that one’s now deprecated and poorly supported).

If you want to dive deeper into how clickjacking works and why XFO matters, Troy Hunt has an excellent write-up here.

X-Content-Type-Options

This one’s nice and straightforward. X-Content-Type-Options has exactly one valid value: nosniff.

When set, it tells the browser not to second-guess the Content-Type you’ve declared for a resource. Without it, browsers might try to “sniff” the file type and override what’s specified in your headers. That might sound helpful, but it opens the door to potential security issues — especially when user-uploaded files are involved.

For example, a file marked as text/plain could be interpreted as text/css or even application/javascript, depending on what the browser thinks it sees. Not great if you’re trying to lock down content handling.

Example header: X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Simple. Effective. No reason not to use it.

Referer-Policy

Whenever you click on a link on a website that redirects you from the original site (the origin) to another site (the destination), the destination receives information in the Referer HTTP header about the origin that you came from. This is how analytics platforms like Google Analytics can tell that 90% of the traffic to my site comes from that one viral LinkedIn post.

The Referer-Policy controls how much of that referral information should be included with the Referer header.

By default, browsers use no-referrer-when-downgrade. This means the full URL (including origin, path, and query string) is sent—unless you’re moving from a secure site (HTTPS) to an insecure one (HTTP). In that case, no referrer info is sent to protect privacy.

Example: Referrer-Policy: no-referrer-when-downgrade

You can configure this header to be stricter or more permissive depending on your privacy and security needs. For the full list of options, check out the official docs here.

Feature-Policy

In today’s mobile-first world, browsers have evolved to support features commonly found on smartphones and tablets, like camera access, microphones, geolocation, gyroscopes, and payment systems such as Apple Pay. These features can be useful but also pose privacy and security risks if left unchecked.

The Feature-Policy header lets you explicitly specify which browser features your site is allowed to use, and which it is not.

If your web app does not need access to the camera, microphone, or payment systems, you can deny these features completely. This reduces the attack surface and helps protect your users from unwanted spying or data leaks.

Example: Feature-Policy: camera 'none'; microphone 'none'; payment 'none'

There is a full list of controllable features. For the complete list, check out:

Feature-Policy directives

Conclusion

Phew, this post was a big one, but we covered a lot of important stuff. Let’s recap.

- “Bank-grade” security is bullshit. You can and should do better.

- You have a shared responsibility to your users. Security isn't optional.

- Use HTTPS, always. No excuses.

- Make sure your SSL certificates are configured properly.

- Use Security Headers to harden your site and control how browsers interact with your content.

The internet was never designed with security in mind. We have pushed it far beyond what its creators imagined. Because of that, securing web applications is hard. Sometimes it feels like trying to hammer a square peg into a round hole. Trust me, I know those feels.

The only way forward is to remember that we all have an active role to play in keeping the web and its users safe. Stay sharp on security best practices, keep up with the evolving threat landscape, and continually improve your defences. Your users and clients will expect this from you.

Most visitors to your site aren’t security experts. They just expect to use it safely without second-guessing if their data’s at risk. That trust is on you. Protect their privacy and treat their information with the respect it deserves—no shortcuts, no excuses. Don't mess it up.

Comments ()